Any comments, contributions, or feedback? Ping me!

Follow @adlrocha Tweet to @adlrocha

@adlrocha - Network Coding in P2P Networks

Linear combinations on-the-fly!

I am not going to lie, writing my Sunday publication is getting harder and harder as I go deeper into my research on file-sharing in P2P networks. I spend almost all of my waking hours working on it, and by the end of the day I don’t have any more brain power left to start writing one of these pieces. Fortunately, I am working on such an exciting field that I can always choose one of the things I’ve been exploring throughout the week and just start writing about it. And this has been the case for this publication, where I will share my excitement about network coding schemes in P2P networks.

The formal introductions

Network coding is a networking technique in which transmitted data is encoded and decoded to increase network throughput, reduce delays and make the network more robust. In network coding, algebraic algorithms are applied to the data to accumulate the various transmissions. The received transmissions are decoded at their destinations, and the original form of the data is recovered. These algebraic algorithms can introduce some overhead, but it allows us to do cool things in the transmission such as sending different pieces using different paths so that as long as the receiver gets a minimum number of pieces it can reconstruct the original data.

Network coding has been shown useful in a great gamut of communication fields: wireless mesh networks, messaging networks, storage networks, multicast streaming networks, and many other scenarios in which the same data needs to be transmitted to a number of destination nodes, including file-sharing peer-to-peer networks. The application of network coding schemes over peer-to-peer networks can be challenging, but luckily, many have “played with it” already, so they were worth a deeper study for the sake of my research.

Avoiding the bottleneck

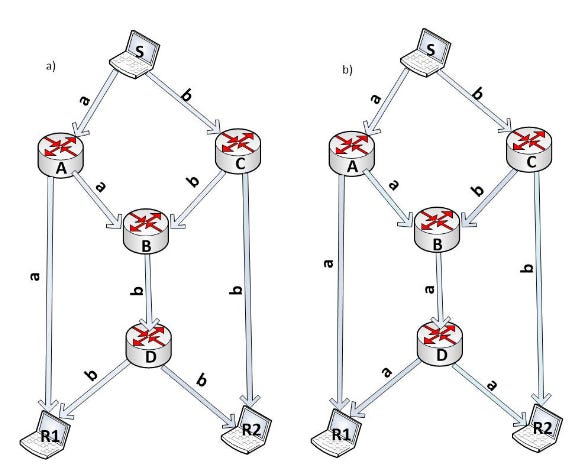

Before we get down to business, let’s illustrate the benefits of network coding with a simple example. Take a look at the network topology from the figure below. Imagine that S wants to send two messages, and , to R1 and R2. S has two peer connections, so it chooses to transmit the two messages in parallel, one through each of its links. A and C broadcast their packets through all of their links flooding the network. R1 receives message through the path S-A-R1, and R2 the message through S-C-R2. The problem arises in the B-D link. B will receive both packets and almost simultaneously, so it will have to choose which one to forward first. If it chooses to forward , R2 will complete the reception of both messages one time slot before than B, and the other way around, if B chooses to forward first (see right figure and left figure respectively).

So S tries to spread the forwarding of its messages through its links in an attempt to load balance and parallelize their transmission, but due to the underlaying topology of the network, a bottleneck is formed in the B-D link that forces messages to end up being forwarded sequentially (instead of the initial intent of S which was to parallelize the load). Even more, under this scenario R1 receives message two times, and R2 two times, leading to duplicate messages, redundancy, and a waste of bandwidth.

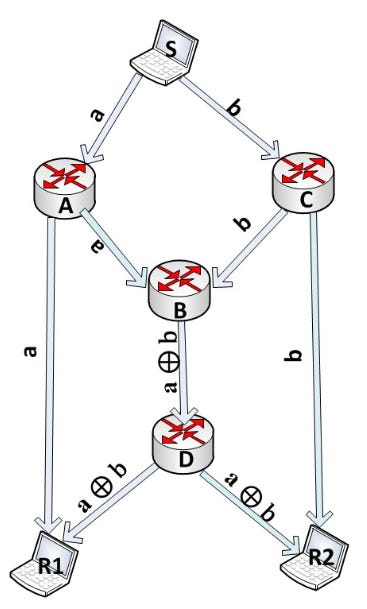

But don’t worry, here is where network codingcomes to the rescue! What if when B receives and almost simultaneously, it applies a simple algebraic algorithm on the fly, such as an XOR, to both messages in order to be able to forward both of them at the same time? Instead of having to send one message after another sequentially, he will be able to send a new packet = XOR . B would forward this message to D, and D would multicast to R1 and R2. Now both, R1 and R2, have and , and and respectively, and with this they can recover the original messages through = XOR and = XOR (see figure below).

Using this simple scheme, the time required to deliver the two messages is decreased in one time slot, while duplicates are removed from the network making a more efficient use of bandwidth. Voilá! This simple trick allowed us to effectively send both messages to its destination in parallel and avoid the underlaying bottleneck.

Of course, this was a really really really simple example. In more complex scenarios, with more complex network topologies, the operations required to achieve these benefits in the network are way more advanced. Some examples of the most used of these “advanced techniques” are, for instance, Random Linear Network Coding (RLNC), and Vector Network Coding. In RLNC the outgoing packets are linear combinations of original packets, so each encoded packet contains data plus coefficients. RLNC can be applied in a distributed fashion, where each node can independently and randomly select coefficients from a Galois field (GF). GF is very useful for practical purposes because each element of the GF can be represented with the same number of bits that guarantees that the result is representable with the same number of bits as the original packets. This scheme is the one I feel is more promising to help me in my project.

No more “missing pieces”

It’s a no-brainer, but in P2P networks there is no single server from which to download all the content we want, we need to ask the network and discover the peers that store the different pieces that comprise the desired content. Consequently, the algorithms used for the selection and transmission of the pieces significantly impacts the performance of file-sharing in the network. Under certain scenarios, we can even face the fact of not being able to download the full content because a piece is either very rare or not available within the network.

The cool thing about this is that with the assistance of network coding, a common issue in P2P file-sharing as the aforementioned one can be partially subverted. Rather than distributing the original data pieces, a peer shares encoded pieces, where each encoded piece is a linear combination of the original pieces. In this manner, there is no need for the requester peer to ask for special data pieces since all encoded pieces are almost equally likely to be beneficial to the peer. A peer in the network can blindly download encoded pieces from other peers without having to worry too much about if it was the one he was looking for. When a sufficient number of encoded pieces are owned, the original file can be reconstructed. Using this scheme, the rarest piece problem is avoided, and the download time of the file is potentially reduced. This is a good example of how network coding can be beneficial in P2P environments.

Many of you may be wondering, “but this network coding technique is pretty similar to the use of erasure coding schemes in piece storage, right?” And you are completely right, both fields are connected and share many of their foundations, but for me network coding is much more than just erasure coding in storage. Rather than just focusing on smart ways of storing content to make future transmission more efficient, network coding techniques can be applied on the fly, so that even if pieces are being stored in raw, without any “fancy” coding technique, peers in-path can be smart enough to combine and accumulate received pieces to try and improve the transmission of content, and make a more efficient use of bandwidth (see the example above).

Applying network coding to a p2p network is not straightforward, and it comes with some penalties in terms of computational overhead. A good illustration of this overhead can be seen in this extract from this awesome paper which shows what network coding can do to BitTorrent nodes if used naïvely:

With network coding, the coded pieces are distributed rather than the original pieces.As the coefficients are received with a piece, they must be tested against all previous sets of coefficients that the peer has received to examine if the new piece contains any previously unknown information. The received encoded piece is said to be innovative if it contains beneficial information; otherwise, it will be discarded. Additionally, decoding the file after receiving enough pieces is more computationally intensive using network coding. The file decoding within BitTorrent is very trivial and simple. Each piece is checked and verified separately; then, it is directly stored on the hard disk. Conversely, the decoding process in network coding cannot be done until all the needed pieces are received. Consequently, decoding the file requires solving many linear equations. As the size of the file increases, the cost of solving these equations increases. For example, for downloading a 3 GB file that is segmented into 1000 pieces, the required disk read operations are 3000 GB on each receiving node. Meanwhile, the BitTorrent system only needs to write 3 GB of data.

So as exciting as network coding can be, applying it to unstructured networks where you can not plan in advance many of the dynamics of the network may not be as easy as it seems.

Let’s wrap up for today

At the beginning of the publication I told you that I was having trouble finding the time to write these publications, but the fact is that once I start writing about a topic I enjoy I can’t stop. The first draft of this article was over 3.500 words long. In its first version I even introduced the five types of network coding techniques that have been used so far in P2P networks with examples, but I had to restrain myself not to bore everyone to death. I think this is more than enough on network coding fot today. If many of you show interest on the topic I can get that long draft back and write a “Network Coding in P2P Networks Part II”.

I really hope you got as excited about the idea of network coding in P2P networks as I did, and that this publication gave you lots of ideas (that you can hopefully share with me to help me in my research). Of course, If I end up using any of these network coding schemes I will let you know and share the results with you :) In the meantime, I highly recommend this paper (which was my main reference while writing this article).

Any comments, contributions, or feedback? Ping me!